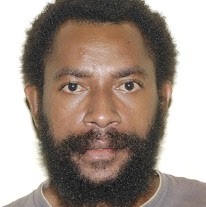

Forestry in Morobe Province - Photo: LWF/C.Richter

By Reuben Mete

Finding solutions to Papua New Guinea and South Pacific difficulties today and into 2050 does not lie in words and more words but in solidarity in word and deed.

I’m humble by the opportunity given to lead Papua New Guinea and South Pacific delegates to participate in this year’s International Leadership Consultation as a Global Youth Leaders gathering for solidarity and to cooperate for justice as opportunities of such are given to voice our concern.

The most compelling witness to the strength of young people in the Papua New Guinea and South Pacific is to be seen as tomorrow leaders having the opportunity to discuss issues affecting them today. Thus, when the weaker members are made strong and well, the stronger members will grow even stronger to maintain their trusting-caring relationship.

1. Insecurity affecting our Societies

Insecurity is one of the latent issues increasingly amongst the younger populations in many of our Pacific Island countries. In most countries, the youth accounts for about 30 to 40 per cent of a population of almost a million people. This is a telling statistic mainly because of the impact it will have not only on services and infrastructure but also on the nature of politics and socio-economic in the near future. Further, our young people are bored. School students have little to do after school. Unemployment is high which means many have nothing to do after they leave school. They wander the streets; they hang around the shops and cinema on weekends. There is an incidence of experimental sex and crimes – girls with babies and boys with guns.

The crux of the matter is there are not enough employment opportunities and hence, they do not feel they are meaningfully participating and gaining from the economy.

Our highly educated young people will turn to violent means to fulfill their aspirations if they stay at home or move overseas.

This will undermine not only our fledgling democracies, but the source of creating and distributing wealth – our economies.

There has been breaking down of the institutions of marriage and family, where recent statistics suggest that about 1 in 5 marriages do not last for 10 years.

Moreover, there is an explosion of squatter settlements in and around the urban centers in our islands. Those who came and settled in these settlements have either lost their land leases or moved because of increasing rural poverty or simply did so to give their children a better chance of quality education and health services that they would not otherwise get in the rural areas. Consequently, there is an increase in the population of homeless and landless families, street children and the violent physical and or sexual abuse of women and children in some of our Island Countries.

Adding to this is a particular development within the area of urbanization and migration. A growing number of people now have two or three homes, in the village, the city and overseas. This may be leading to some confusion in the values because of the strong possibility that children will grow up with uncles and aunts rather than parents. The generation affected by this will soon form their own sub-culture thus contributing to a context of insecurity.

2. Climate Change in our Societies

There is the issue of climate change and sea level rise that is threatening the very existence of some of our people. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has declared that our region is three times more at risk to climate change than the developed countries of the north.

The World Health Organization (WHO) regional advisor to the Pacific reported that up to 10,000 people will be affected or could be dying each year as a result of factors associated with global warming such as severe weather and mosquito-borne disease. Moreover, the number of deaths due to natural disaster – droughts, floods and storms – increased by 30 to 40 per cent.

Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Samoa, American Samoa, Tonga and recently Solomon Islands, have certainly seen our fair share of devastating cyclones, tsunamis and floods in recent years. It is interesting to note that a new phenomenon is emerging and that is what some called climate induced resettlement.

However, climate change just does not endanger human beings and their socio-political environment. It equally threatens to obliterate many life forms that the natural and human ecosystems depend on for survival and continuity of existence. As John van Klinekn notes, “…from 1850 – 1950, one animal species vanished per year. In 1989, it was one per day and in 2000 it was one per hour. Within 50 years, 25 per cent of animal and plant species will vanish due to global warming and climate change,”

Yet, it is not climate change as such but the unchecked intrusion of human beings, often driven by greed for wealth and power, into the delicate balance of natural environment; from indiscriminate logging and mining to over consumption and inappropriate application of bio-technology. The disturbing and yet challenging lessons here for us, as young people, is that we cannot afford to deny the gravity of the present ecological crisis.

In religious language, as Ed Ayers writes,

“God has given us an offer: to see the consequences of our actions and assume moral responsibility for them, or to be consumed by them.”

This is an offer that we cannot afford to ignore.

Pacific Leaders in various sectors of our island nations – governments, churches, NGO and civil society groups; have expressed concern that Pacific communities contributes very minimally toward global warming and climate change, and yet we are amongst the most affected and vulnerable. The eroding of shorelines due to sea level rises is not simply about geomorphic changes. Rises in sea level and the resultant eroding of shorelines have direct effect on people’s lives in many ways. In part, one can agree that the growing despair among our people has to do with the sheer pace of the changes we are experiencing now. And consequently, a huge gap has opened up between the transformations happening around us and our people’s ability to respond.

It is a state where the material culture such as technology, is being transformed faster than non-material culture such as the modes of governance and social norms. When the external (material) world is changing faster than the internal (ideology and spiritual) world – in our mental and emotional response; our environment becomes intensely bewildering and threatening. Societies take time to change and so do people. The point is that while we and our people may be adaptive we are not made for constant and relentless change.

3.Breakdown of the institutions of social life

Another more significant factor, which alluded above is the breakdown of the institutions of social life, and hence the increasing loss of a sense of permanency.

In the past, our people were helped to cope with change because we have what Alvin Toffler calls “personal stability zones” or can be referred to as “life anchors”.

These were aspects of our lives that do not easily change, if at all. Of these, the most important were a job for life, marriage for life, and a place for life. Not everyone had them but they were not rare. These gave our people a sense of economic, personal and geographical continuity and permanency. Today, however these things are increasingly hard to find.

Role play of a youth group in Lae - Photo: LWF/C.Richter

Paid job are become less permanent and employment in general is increasingly part-time, short-term and contractual. Marriage, as religiously and socially accepted and recognized by law as between man and a woman, and which is the very matrix of community for any society, is being eroded by serial relationships, same sex unions, cohabitation and divorce.

The very concept of belonging to a village, a community, a neighborhood – somewhere we call home; is slowly disappearing. Our people travel and move often in search of work and employment, and or for better healthcare and educational opportunities. The result of this increasing fluidity of our existence in the region is that we face an increasing level of uncertainty with the minimum of resources to protect us against insecurity and external changes.

Change has become systemic and consequently we begin to feel that we no longer have control over our lives. Such a situation gives rise to what social scientist call “social poverty”. It relates to the degree of apathy or indifference to the plight of the most disadvantaged among us.

Up until now, our neighbor is the one who shares our ethnicity, denomination, and religion. That works well when our horizons do not go beyond the boundary of our village or settlement. We know exactly who we are, our role and our status; it was on these relationships that our ethics were constructed and applied. However, when our world becomes larger than our villages or settlements as it is now, ethics becomes more problematic. As young people of Pacific, our response to these deep underlying changes and challenges may become an oppressive burden.

Our response cannot lie at the level of detail, faced with choices as we are now, our people need wisdom. Our young people are one of the rich resources at this time. It sustains reflections of our place in nature and what constitutes the proper goals of our societies and personal lives. It builds communities; shape lives and tell the stories that explain us to ourselves. It frames the rituals that express our aspirations and identities. We must now possess the power to choose, act and take responsibility for our destiny.

4. Conclusions

Revolutionary, yet extraordinary about rediscovering our self as young men and women – future leaders for tomorrow.

We must reclaim the belief that the source of action and responsibility lies within ourselves. That is the first step.

The second step is we should start think globally and to think of humanity as a single moral community linked by mutual responsibility. Our present Pacific context compels us, as young people, to seek a new way of engaging with our people’s struggle for meaning and purpose. Because we are not products of forces beyond our control, we need a moral vision that situates the source of action and responsibility within ourselves. The construction of such a vision will, therefore out of necessity, include the key values of human dignity, justice, compassion, hope and peace.

5. Suggestions and Consideration

Firstly, there is a need in a Youth Network Program on formation in ethics and morality, governance, social justice and stewardship at the International, Regional, National and Local Levels. However, such a program would be more than just another meeting or conference but would involve lifestyles and perspective changes over a number of years.

Secondly, there is a big need to encourage Youth population to participate more actively on this journey. The older we are, the deeper our roots are in the past and the less able we are to see ways in which the future is developing.

Do we want to keep hearing opinions from the past or aspirations for the future?

Reuben Mete, Youth Leader of the Evangelical-Lutheran Church of Papua New Guinea

Views expressed on this blog are the opinions of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion or positions of The Lutheran World Federation.