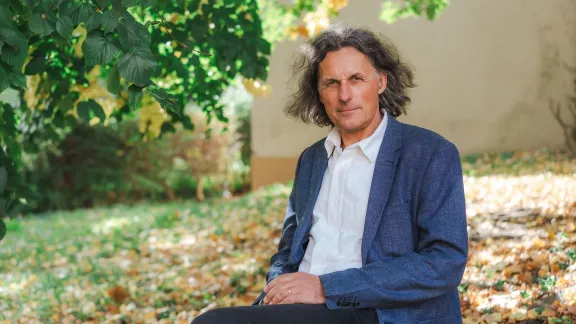

Rev. Dr Pavel Pokorný, Synodal Senior of the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren at the 8 to 11 October European Regions’ Meeting in Prague. Photo: LWF/Šárka Jelenová

Synodal Senior of the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren Pavel Pokorný reflects on hope in an uncertain future

(LWI) - As a young boy, growing up under communist rule in Czechoslovakia, Pavel Pokorný was influenced by both the Protestant church that his family attended and his father’s passion for the natural sciences. Both helped to shape an enquiring mind, open to doubts and questions, searching and discovering new insights into the details of people’s lives, but also into the wider perspective of the cosmos and our place in it.

An intense encounter with a youth community during his high school years marked a turning point, as he felt called to ordination in order to share with others the freedom he had found there. It was the start of a journey which has led him to leadership (Synodal Senior is his official title) of the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren, the largest Protestant church in the Czech Republic.

Ministry with the elderly, hospital and hospice chaplaincy and work as part of an ecumenical team have all been important milestones on that journey, says Pokorný, as he reflects on the future of Christianity in his increasingly secular Czech society

Tell me something about your family background?

Yes, the history of our Protestant Christian family goes back to the 16th century. Our ancestors were Hungarians who came to the Czech lands after the Patent of Toleration (granting religious freedom to non-Catholic Christians living in the Hapsburg empire). But there are other branches of the family coming from the Czech countries, so we are a mixture, like almost everybody living in Central Europe, I think.

My family was rooted in the church and my parents were very active in congregational life. My grandfather was a pastor, but my father was a geologist which was also very inspiring for me because his perspective was that of the whole cosmos developing throughout millions of years. He liked to talk to me and my brother and two sisters about his scientific way of thinking, that is doubting and asking questions, again and again, to discover new things. I think that is also a good way for us, as theologians, to be flexible in our thinking.

You grew up in the church then, but within a very secular, communist society?

Yes, I am a believer and I had many friends who were not, but we just did the crazy things that young boys do and I didn’t feel any differences. It was like the identity of a child growing up bilingual, feeling at home in both communities, not threatened by either of them.

It’s the same today: my Christian identity is crucial to me, but that doesn’t mean there is a fatal gap between myself and secular people that I meet because we all have things in common and things that are different.

When did you decide you wanted to become a pastor?

When I was about 17, I joined a community which was loosely connected with the church, but it was a very informal group of friends that was open to other young people and run by two ministers. We gathered on a farm in the countryside and during those times of totalitarianism, this was for me a community of freedom – an island of free speech and mutual trust, where we talked about the substantial issues of life.

I realized that these ministers were not so much leading the group, but they were there in the background listening, understanding, supporting and I could see that without them, there would be no community. This was such an intense experience that I decided to study theology because I thought this was something precious that should be continued for others who will come after us.

Where and when did you do your studies?

I started my studies in 1979 in Prague, which was, and still is, the only Protestant theology faculty here. I was ordained in 1987 but before that I had to serve two years in the army which was rather demanding. I had no contact with my family and my community and at that time, theology students were seen as opponents of the communist regime, so we were watched very closely and it was not pleasant at all.

Where was your first parish after your ordination?

First of all, I went to Eastern Bohemia to the so-called Sudetenland, where the Germans, who had settled there, were expelled after World War II and Czech people from other parts of the country came to live. It was a very special mix of people who didn’t know each other and didn’t trust each other because of the communist party’s rule of terror.

So when I arrived in the late 80s, I found people in my congregation who didn’t speak to each other. When I visited the elderly people in their homes, they often said ‘we are not at home here’. It was terrible: they had lived for 40 years in a place that didn’t feel like home. I felt so helpless – what could I offer these people at the end of their lives?

For me, this was an experience of how political and historical changes can have an impact on a whole generation. But it was also a great school for me, because I arrived fresh from my studies thinking that now I know how to preach and explain everything to people. I stayed for 12 years and it was really an important school for me.

You also went to study in the United States, didn’t you?

Yes, because of this experience of how difficult pastoral care can be, I felt that I was not competent enough and I wanted to study and reflect on this. I went to Texas to the Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary and did my practice in hospital ministry. When I got back to Prague, I was asked by the Central Council of my church if I could be part of an ecumenical group that was establishing hospital ministry in the Czech Republic, because this was not possible during the communist era, of course.

Although I had experience in the U.S. hospital, it was very different in Czech hospitals, so I took a part time job in a hospital and became a member of this ecumenical group. We prepared the national health care pastoral system and it was a very interesting ecumenical experience of just being pastors together, mainly Protestants and Catholics, serving people in need in the hospitals.

What are the challenges of being a pastor today in the Czech Republic, which is one of the most secular countries in the world?

I think there are so many different perspectives, even though most people are not members of the church. If you talk to them, you find that many have personal beliefs that are quite similar to our Christian beliefs, because this was a Christian country and I think that, on an unconscious level, this somehow still shapes the imagination.

Then there are those who follow Eastern religions, or those who believe in all kinds of esoteric or New Age religions, as well as those who have a very secular or materialistic mentality. I think this may be similar in other traditionally more Christian countries, but it is a bit hidden under the surface. I think, in our case, this can be an advantage, that people do not have to pretend but they tell you clearly if they believe or not.

In this context, what is the role of the church which you are leading?

I think that because there are so many different perspectives, there are also plenty of possibilities and we have to look for these different ways, but they must be very personal, very individual. I don’t expect much from big campaigns, but I believe more in very small, personal and pastoral missions. That means being really interested in who people are and what they are struggling with.

I think the role of the church in the public space is to be a voice among others, not preserving our own institutions, but standing up for the weak. We must find the courage to trust and to remember that we belong to Christ, but Christ does not belong to us.

Are you hopeful for the future of the church then?

As well as working as a hospital chaplain, I also served in a hospice and had to think a lot about the meaning of hope. In a biblical sense, I think hope is a kind of gift from God and does not depend on any measurable facts. I like my church as an institution, with all its traditions, but I think that even if it does not have a future, for me this doesn’t mean that the Gospel, God’s story with the world and with humanity, will come to an end. I am hopeful, because my hope goes beyond the present world and beyond our own tradition.

What does it mean for you to be a part of the global communion of churches?

I don’t see an impact on my daily life, but whenever we meet in a broader context, it helps me to see this whole Christian community which encourages me a lot. It opens up a broader perspective and I think on an emotional level, as much as an intellectual level, it gives us a feeling of being connected and helps me to reflect upon my work and my testimony – our testimony as church in the Czech Republic.