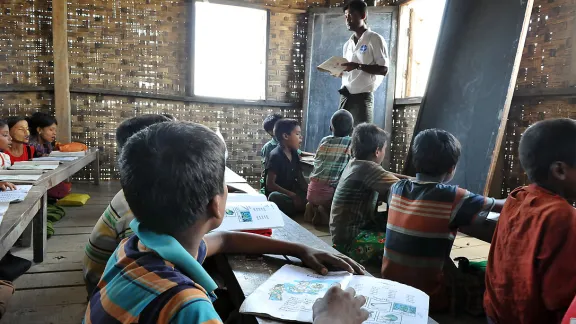

Children in one of the Nget Chaung-2 school rooms. These temporary classrooms constructed by LWF are the only school they are currently able to attend. Photo: LWF/ C. Kästner

LWF supports communities with schools, teacher training and student kits

(LWI) - The noise of 150 primary school children in one room is deafening. In colourful clothes they sit on the floor of a “Temporary Learning Space” (TLS) in Nget Chaung-2, a camp for internally displaced people near Sittwe, the capital of Myanmar’s Rakhine state. The TLS is an informal school, as the students are not allowed to access public schools in Myanmar.

Many of the children have their faces painted with Thanaka, traditional makeup. Applied in playful swirls and patterns, it is protects them from the tropical sun and heat. In front of them, on the small desks, they have set the LWF branded traditional bags with their precious posessions: Exercise books and pencils which they received from The Lutheran World Federation (LWF) in Myanmar.

On-going ethnic tensions

Nget Chaung-2 is one of many IDP camps in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. Long-standing ethno-political-resource tensions between the Buddhist Rakhine and the Muslim population, which continue to erupt in violent clashes, have led to displacement of especially the Muslim population. Many among the Muslim population do not have citizenship rights, consequently many children in the school have no birth certificates, and little or no access to public schools or later formal vocational training.

The camp is home to 3,335 Muslims in Myanmar who were driven from their homes in the communities of Nget Chaung, Don Ywar and Lumbardiain in 2014.The camp stands out because of its isolated situation on an island. A 45 minute speed boat ride from the west coast of Myanmar, the camp can only be reached by balancing on narrow muddy paths through tidal flood plains. The nearest health facility is a 15 min walk away. The houses are standing on stilts because the camp gets flooded regularly.

LWF is assisting people in Nget Chaung-2 with camp management, community and protection services, and emergency preparedness. LWF has trained the inhabitants in fire safety and set up a link to the Sittwe fire department. LWF also facilitated the installation of latrines.

Education and vocational training are the greatest interventions in the camp. LWF runs a non-formal education center where 189 women currently receive literacy training, and has constructed five temporary learning spaces for primary students as well as child-friendly spaces for pre-school children. For this purpose 28 teachers were trained and 1,100 students have received schoolbooks and bags.

Tentative relations

The learning conditions are nowhere near ideal. “We teach in two shifts,” says Maung Kyaw Naing, a community teacher. Two classes share the same space and they sometimes try to out-shout each other as they are asked to repeat poems or the letters of the Burmese alphabet on the blackboard. “We tried to partition the room,” he says, “but it became unbearably hot.”

His students do not talk about the violence that led them here, he says, but the living conditions impact on the school performance. “Many students have difficulty concentrateing,” the teacher says. “They do not have a place to studyat home, after sunset, there is no light to do homework. Everybody eats and sleeps in the same space.”

At the same time, relations with the Buddhist communities continue. “We cannot leave the camp, so they come here to trade with us,” the teacher says. As the inhabitants are no longer able to farm as they used to, the only possible income comes from crab fishing in the murky water surrounding the camp.

“We want to go back to our village,” says Maung Hla, chairperson of the camp management committee. “There is no privacy here, nothing, just the fishing. We lost everything. We cannot move freely.”

Education and citizenship

The movement restrictions also impact the children’s education, Maung Hla says. “One of the problems is that we do not have a secondary school. By now there are 85 secondary schools students. It costs 10,000 Kyat (7.45 USD) to take the boat to the school in Sittwe. We mentioned that to the government, but haven’t gotten a reply yet,” chairperson Maung Hla adds.

It is the central government which decides teacher deployment, U Aung Kyaw Thun, the state director of education in Sittwe, points out. As tensions are high between the communities, he will not send any of the Rakhine teachers to the Muslim camps. “One of my friends was killed in 2012,” he says.

Above all the issue of education in Pauk Taw IDP camps is one of citizenship for him. “It needs to be decided whether they are citizens of Myanmar or not,” he says. If it is clear that they are citizens, then we can implement something for education. At the moment, I fear for the safety of my teachers.”

The LWF program on education in Emergencies and Education Development ensures learning possibilities for students aged 3 -17 in Myanmar. The program currently supports 7,056 students in formal Rakhine schools and 8,198 IDP children in Muslim communities.

LWF assistance encompasses early childhood development, primary, non-formal and life skill education. This involves the construction and maintenance of temporary learning spaces and child-friendly spaces, provision of teacher and student kits and facilitating safe access to educational needs.

LWF’s work in Myanmar has received support from ECHO and FCA, UNICEF, EU and Church of Sweden.

By Cornelia Kästner/ LWF communications