Posters, like the one held by counselor Pradeep Subedi, show the psychological impact of earthquakes on children. Photo: LWF/Lucia de Vries

Psychosocial support for earthquake survivors

(LWI) - It is Saturday morning in Ghusel, a village almost completely destroyed by the earthquake that struck Nepal half a year ago. From the village square the sound of a harmonium can be heard. Soon a tabla (drum), tambourine and Nepali drum join in. Then some voices pick up the tune, and a religious hymn echoes across the hills of Lalitpur district.

Krishna Kumari Mahat is one of the 50-odd villagers who gather here once or twice a week to sing devotional songs. “I used to listen to bhajans (devotional songs) on the radio. Singing them myself with my friends makes me proud and happy. My favorite ones are those for Lord Krishna. I just wished I could do this every day,” she says.

Total destruction

In Ghusel the physical impact of the earthquake is still visible. All but five of the 355 houses were reduced to rubble or sustained major damage. Villagers live in makeshift shelters, built with pieces of wood from their former houses, bamboo and tarpaulins. Five people died and nine sustained major injuries.

The unseen effects of the disaster are harder to spot. The massive destruction that took place on a sunny Saturday afternoon last April has left scars that will take time and sometimes professional support to heal.

Among the reported psychological impacts of earthquakes are post-traumatic stress disorder, adjustment disorder, anxiety attacks and depression. Most people who experience acute stress and ongoing fear and uncertainty due to recurring aftershocks will recover naturally over time. A small number, however, will suffer ongoing psychological distress and will need support.

Take people’s minds off the disaster

Communal gatherings like the ones in Ghusel are an important form of intervention by The Lutheran World Federation (LWF) Nepal. LWF as part of the ACT Forum nepal is conducting a psycho-social support program in five districts affected by the earthquake. The program consists of community-based intervention, workshops and referrals for medical aid.

Community-based interventions aim to take people’s minds off the earthquake - and the many problems they have faced since - and to express themselves more freely. Through recreational activities aimed at different age groups, sharing and expression is encouraged.

The elderly generally prefer singing and are provided with musical instruments. For children art and music activities in the local school are offered. Among the young people, sports is the most popular. Women’s groups receive support to organize singing competitions.

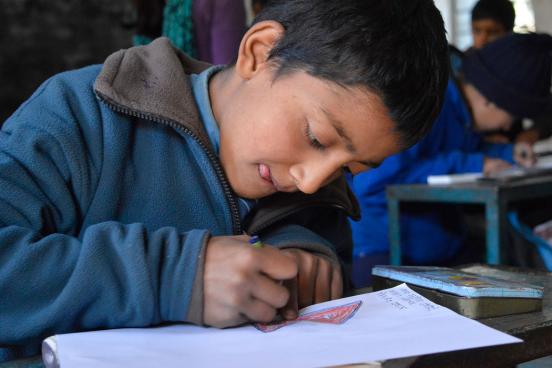

Ghusel school was one of the many buildings that collapsed during the earthquake. The more than 200 students from the village now study in temporary class rooms, built with bamboo and tin sheets. The buildings are dark and cold but on Fridays the atmosphere is lifted with a different kind of curriculum.

Since LWF Nepal provided crayons and paper, students gather at the end of the week to draw. Most want to take their drawing home, to show to their parents, but some agree for their art to be put on the tin sheet walls of the school. The smaller children are led to sing fun songs, accompanied with gestures to emphasize the words. The songs evoke many smiles, and much clapping.

Mental health surrounded by taboos

“When we think of psychosocial support we usually only think of counselling,” says Pradeep Subedi, the LWF psychosocial counselor based in Lalitpur district. “But in a country like Nepal, where mental health is still surrounded by taboos, it makes sense to embed it in community activities.”

Subedi knows first-hand about mental problems. He has been suffering from hemophobia or an extreme fear of blood since childhood. “I considered myself a failure until I looked up my symptoms on the internet and realized I share my condition with millions of people around the world.” Subedi changed his studies to psychology and joined the LWF program in Nepal after the earthquake.

LWF organizes workshops for village leaders including teachers, volunteer health workers, traditional healers and youth leaders, introducing themes like mental health and the importance of professional support. Subedi has referred five people from Ghusel and a total of 65 from his district for professional support. “That might sound like few, and it is indeed hard to measure the impact of our work,” he says. “But from the feedback of the people we conclude that the program is helping earthquake victims recognize and deal with psychological distress.”

Interventions such as these are backed up by a national radio program called Bhandai Sundai (Talking and Listening) which provides earthquake survivors an opportunity to ask questions and share their grievances, fears, trauma and concerns on air.

Uniting the village

After the singing workshop, Krishna Kumari returns to her makeshift shelter. “I am very worried about our house, how and when we will rebuild it, if ever,” she says. “I also worry about the cold, and my grandchildren’s education. But when I sing I forget my worries for a moment. I feel united with the other villagers, who all experienced the same thing. The village had to wait for 15 years to be able to unite and sing bhajans. It’s one good thing that came out of the earthquake.”

“Come back next time,” she adds. “I will be much better by then.”

Contribution by LWF Correspondent Lucia de Vries, Nepal

Visit the Nepal earthquake response page, the Nepal program page and the Nepal program site