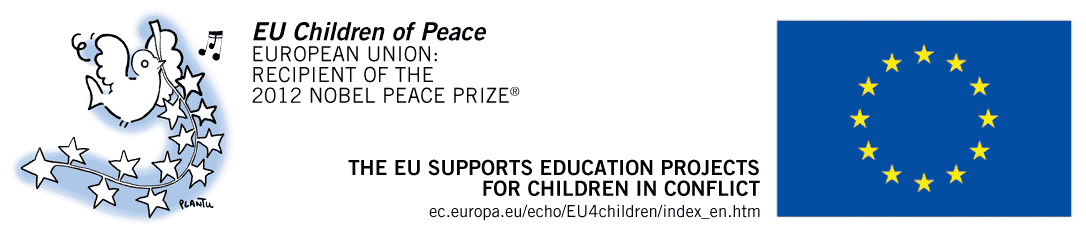

ALP students at Napatat Primary School, Ajuong Thok refugee camp. South Sudan. Photo: LWF/C. Kästner

Students in a South Sudanese refugee camp embrace education

(LWI) – “I came here to learn”. 18-year-old Mobarak Habil Ibrahim introduces himself. He fled the conflict in the Nuba Mountains, Sudan, and left his parents. His temporary home is Ajuong Thok refugee camp in South Sudan.

Mobarak does not know when he will be able to return, but like his classmates, he is determined to make the best of his current situation. “We faced many problems. We have war in my country, our enemies attacked us. So we have come here to learn, to get what will benefit us in the future,” he says.

Schools at home destroyed

The Lutheran World Federation (LWF) is the sole implementer of education in the expanding Ajuong Thok refugee camp. LWF is running three primary and one secondary school as well as child rights clubs and seven child friendly spaces, something like a day care for children of all ages. One was set up for the host community which at one point demanded equal education opportunities as were given to the refugees.

The Accelerated Learning Program (ALP) which Mobarak and 1,800 students are attending is a special intervention for over-age learners who have missed part of their primary education due to conflict and displacement. The program helps them to catch up and eventually join their peers in secondary school.

Education opportunities are the main reason for refugees to come from Yida refugee camp to Ajuong Thok. “It is very important to the Nuba people,” LWF Education Coordinator Annet Kiura says. “The conflict has destroyed the schools in Kordofan. When the students come here, they are eager to learn”.

In the morning the three Primary schools resound with the noise of more than 2400 students, while younger children carry their baby siblings to child friendly spaces to learn the alphabet and their first English words through songs and play. There is a long list of open teacher positions at the headmaster’s office in Napata Primary school. Like their students, the teachers come from Kordofan. They now teach in English and according to the curriculum set by the South Sudanese Ministry of Education.

New challenges ahead

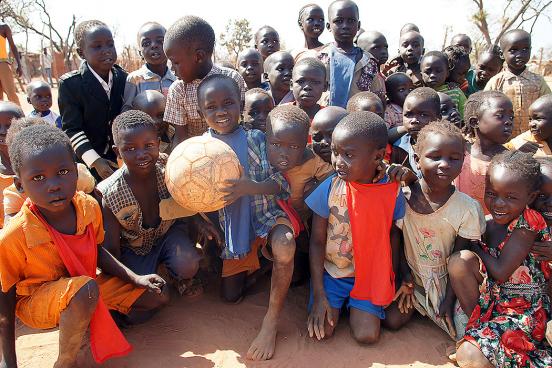

Visit Soba secondary school after school hours. In the afternoon heat, the tents which were set up as temporary classrooms are filled with students. Music is playing quietly while the teenagers are revising and doing homework. A student shares his notes from the science lesson on the big blackboard, the others copy carefully into their books.

The students sit on homemade benches made of logs, and write on their knees. There is an atmosphere of quiet concentration; newcomers join without making a sound. The only unruly thing is felt pen writing on the canvas of the tent. “Life isn’t easy” it reads, and: “Never give up!”

Mobarak, like many of his classmates, wants to become a doctor. He loves science and maths. Others strive to be teachers, engineers and pilots. “There are many things I did not know in the Nuba mountains” Mobarak says. “But when I came here, I learned. We found hospitals and secondary schools. Here everything is good”.

Since the conflict in the Nuba Mountains escalated, Ajuong Thok saw an increase of refugees. The camp, once set up for 10,000 refuges, had 21,000 inhabitants by mid-February. 1,000 people arrive every week. UNHCR estimates that the camp will hold 40,000 people by the end of 2015. Half of them will be children, 43 percent of them of school age.

Make a difference

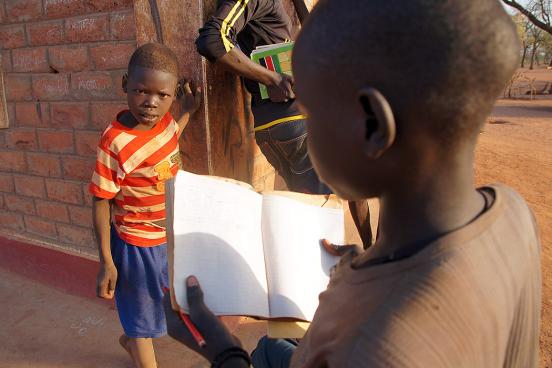

It is up to LWF to meet this challenge. Already classrooms are overcrowded, with one teacher for 70-100 students. “We need at least twice as many primary schools and another secondary school” LWF team leader in Ajuong Thok, Anne Mwaura, says. Resources however are hard to come by.

Due to the volatile security situation in South Sudan, everything has to be delivered by expensive air cargo, which has raised operation costs. The trucks which were meant to bring school desks, books and play material for the child friendly spaces last spring got stuck during the rainy season and now only slowly make their way through checkpoints of different conflicting parties.

Still lessons continue, even during holidays. “Education is one of the interventions to keep children from risk, girls from getting pregnant and boys from being drawn into forced labor or even recruitment,” Mwaura says.

Malachi Farouk Aballah, the ALP head teacher, hopes to raise a new generation for his country. “It is very important for them to acquire knowledge and skills,” he says. “When they finish they can get good jobs. Some of them will be teachers, they can teach this country”.